Both the approach and its policy implications have been heavily criticised. Some of the more important points are simply highlighted here.

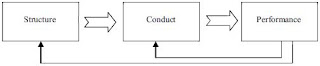

– Assuming that there is a causal chain, it would supposedly not be unidirectional: performance would have repercussions on the number of market participants, hence on market structure.

– Correlations are not necessarily causal chains. High profitability could, e.g., also be the consequence of lower production costs. If low production costs enable a firm to capture a large market share, one would indeed expect a high correlation between market share and profitability.

– There is a very small number of actions that can be said to always be conducive or always be detrimental to competition: price cuts have often been said to be part of a predatory strategy, yet they can be a sign of fierce competition that forces firms to lower their prices to reflect marginal cost. Observing conduct will, in other words, seldom be sufficient to establish that competition is not workable in a particular market.

– The number of criteria for the market performance test is very high. This means that criteria need to be prioritised, be attached certain weights, etc.

– Representatives of a procedural approach toward competition would claim that “competition is a discovery procedure” (Hayek 1978) and that its results are therefore systematically unpredictable. Neither the optimum number of firms in a market nor their optimal conduct can be known ex ante but have to be discovered by the competitive process. The interventionist stance promoted by this approach would therefore be inimical to the very basis of a market economy.

– The possibility of widespread interventionism is detrimental to predictability, the criterion identified as crucial for a good competition policy in chapter I. This becomes very apparent in the following quote (Kantzenbach/Kottman/Krüger 1995, 25): “A structure oriented competition policy often reduces the level of planning security.” Kantzenbach is the most influential adherent of the Harvard approach in Germany.

Especially in its heyday, the 1960s, the paradigm was highly influential. When its followers observed some action that was not immediately explainable, they supposed the action was undertaken in pursuit of monopolising. That firms were trying to economise – and thus to increase welfare – did often not even come to the minds of those who believed in the paradigm. In the early 70s, the later Nobel laureate Ronald Coase (1972, 67) wrote: “If an economist finds something – a business practice of one sort or another – that he does not understand, he looks for a monopoly explanation. And as in this field we are very ignorant, the number of ununderstandable practices tends to very large, and the reliance on a monopoly explanation frequent.” Barriers to entry were another obsession of the representatives of this approach. We will deal with them in some detail in the third section of this chapter. Before, we turn to the so-called Chicago approach which can only be understood as an answer to Harvard: Whereas followers of the Harvard approach suspected monopolizing practices just about everywhere, followers of the Chicago approach turned the whole story squarely onto its head: they explained just about every behaviour with underlying efficiencies.